At the beginning of October 1990, I arrived in Johannesburg for the first time. After months of nagging, the South African embassy had issued me a visa. I had never bridged such a distance flying. I was extremely nervous. Changing flights in Rome, I found myself amongst a herd of Afrikaners singing Sari Mareis. Then the airplane took us back to the old Transvaal. Upon arrival the sign Verbeteringe in Wording – Under Construction – struck me. Next to a display of weapons. A visitor’s guide to How To Recognize a Terrorist?

I was picked up by Jasper Cook, the only white musician in the band of the African Jazz Pioneers, whom I got to know in 1987 during Culture in Another South Africa – an event that brought together around 300 South African artists from exile and home, South Africa, in Amsterdam. Jasper likes to tell the story that at the time I refused him access to a dressing room in De Melkweg because he was not black. I think he confuses me with someone else but it’s a nice story and I don’t contradict him.

What did I see those first days in the promised land?

Johannesburg was a city of protest. And jazz. Cynicism. And Verbeteringe in wording. An irresistible gay nightlife and the mundane Yeoville, the neighborhood in which I would later settle, both slowly changing colours. After a few days I already knew: this is where I want to live. Witnessing perhaps the greatest transition of the late twentieth century. Report on it.

On our way from the airport to town, Jasper said it was a pity that I had arrived late; two banks were robbed that morning in Yeoville. “You should have seen it!” The day after my arrival I joined in the first Gay and Lesbian Pride March, surrounded by many black and white youngsters with paper bags over their heads. In the evening I explored the Skyline, a gay bar of which my partner-to-be Simon Nkoli had already told me during a visit to Amsterdam. After five minutes, someone asked: “What are your plans for the night?”

Help!

The day after the African Jazz Pioneers played in the basement of a run-down hotel. Through the corners of my eyes I recognized Cyril Ramaphosa and Jay Naidoo in the audience. A day later people marched through the city center. Slowly running men and women who kept raising their knees and shouting “oef”. Toytoy. Exhausted from all impressions, I was kept out of sleep by the fireworks of the late evening that sounded in Amsterdam only around New Year’s Eve.

When I told my hostess, Jasper’s sister, about it at breakfast, looks of incomprehension were my share. Fireworks …?

She didn’t make me wiser than I was. And also when I told her that I was going to walk downtown in the evening to find a restaurant and have a bite, she suppressed the commentary that was evident from her visible astonishment. Walk? A restaurant in the town? Only later I understood that eating out in suburbia meant driving to a shopping mall and hide.

During those first three weeks in South Africa I saw more protest than I had participated in all my life in Amsterdam. Everywhere there were debates in which all aspects of the multi-complexity of this intriguing transition process were discussed. Dozens of South African friends and comrades who had visited the Netherlands in the years of anti-apartheid activism took me by the hand and took me around. Invited me to eat and dance and drink. Drink a lot. I had overcome the fears of traveling far after three trips. The traveler’s checks were replaced by a credit card.

Meanwhile, Dutch television showed the images of violence and massacres, suspended negotiations, men suddenly shooting in the train from Soweto to Johannesburg. Third force – a furious Mandela.

It had of course not escaped me in Johannesburg. Sometimes I was on the battlefield itself. The disaster dripped from front pages of the South African newspapers and I devoured them. In 1991 I visited the funeral of Linda, one of the first victims of AIDS. I would do the same at least 25 times in the years that I lived there.

Still, I didn’t know what to do with the worried looks of friends and family in Amsterdam when I set off again. After returning, the question was always how it had been. “Great,” I said, reading the impossibility on their faces to reconcile my enthusiasm with the images they had seen on television. Eventually I muttered something incomprehensible because how do you explain that love wins in times of cholera? That your own coming of age takes shape in a country that is still obsessed with anti-gay laws. That you feel safe where danger seems to be all over. Where you dive into a pool full of people of all colour, escaping an Amsterdam white hub, in a land still so segregated? That you’re in a laboratory where everything bursts and yeasts and sometimes things explode.

Even with South Africans I did not have to come up with that observation. Because who wants to live in a laboratory?

Perhaps the confusion appeals to me the most. That intense search for what must ultimately become a society, a samen-leving. That, ultimately, the issues – excusez les mots – are no longer black and white. “I don’t have to go to Soweto,” a Dutch visitor once told a friend. “I don’t want to watch poor people.” Eventually the man went along anyway. On the terrace in Vilakazi Street, a street that produced two Nobel Prize winners, he observed the waBenzi, the black professionals in fast cars who revisit their roots during the weekend. The man said: “You can’t earn a car like that with honest work, do you?”

Johannesburg is Barbara Harmel, Simon Nkoli, Paul Mokgethi, Basil Jones, Adrian Köhler, Philip Masai, Raymond Matinyana, Beverley Ditsie, Gerald Kraak, Totsie Memela. Dorothy Motubatse, Graeme Reid, Edwin Cameron, Hugh Lewin, Gregory Maqoma. Thuli Madi, Piers Pigou, Mark Gevisser. Venitia Govender, Mpho ‘Tommy’ Diniso. Jacob. Donald. Themba. Ellen. Ivan. Evelyn. Maria. Pretica. Raj. Mabel. Peter. Peter. Peter. Mandla. Lucia. And. And. And.

Johannesburg is poor and rich. White and black. City and suburb. Past and future. Tradition and modernity. Stagnation and progress. Everything comes together in Johannesburg.

It is pure gold.

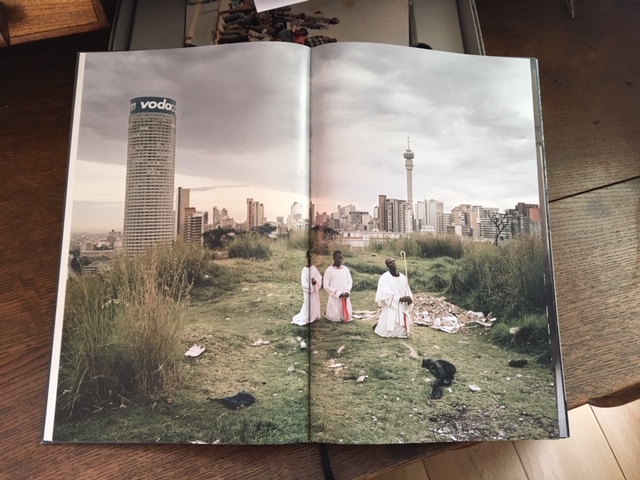

[ Image: Mikhael Subotzky. Final question at the Zuid-Afrika Huis event: “What is your favorite spot in Johannesburg? I said: the Yeoville Hill. The green, the worshippers, the 50 stories high Ponte Tower were my view half of the almost 20 years I lived in Johannesburg. Subotsky’s book in my Amsterdam living room is a constant reminder of those days ]

This is an edited version of a blog that I read at ‘Johannesburg. City of a 1000 Faces’, a conversation with William Kentridge, Gregory Maqoma, Ilvy Njiokiktjien, Nichoas Clarke, Margriet van der Waal and me, Friday 31 May, 2019.

Mooi verhaal, Bart. Dankjewel

Jeetje, zelfs als niet-correspondent en als hetero herken ik dit verhaal helemaal. Mooi opgeschreven, Bart. Enne, je zult toch nog wel eens terug moeten, vrees ik. Of had je al plannen? Wat die mafkees betreft, ik doel op Jasper, die houdt er natuurlijk van om mensen ietwat op stang te jagen. De enige die tijdens CASA de autoriteit had om artiesten al dan niet de toegang tot het theater of de kleedkamer te weigeren was – met permissie gesproken – ondergetekende. Dus dan zou ik hem geweigerd hebben… Geintje. Wel klopt het verhaal dat ik Sean Bergin, de forse, witte, zeer Zuid-Afrikaanse saxofonist die zich met geweld langs de beveiligers van de Melkweg wilde wurmen, vloekend en wel, aanvankelijk de toegang ontzegde. Maar hij raakte zo over de kook dat hij iedereen opzij duwde en mij als ware hij een mannetjes neushoorn torpedeerde en zo binnen wist te komen. Briesend en wel. Ik had hem nog nooit zien spelen, dus wist ik veel… Hij wilde perse meespelen met de Pioneers, wat prima was natuurlijk, maar hij vergat de omgangsvormen omdat hij zichzelf als een heel beroemd musicus zag. Wat hij niet was. Is dat waar Jasper op doelt..? Ik weet het niet, en het doet er ook niet toe, we zullen het nooit weten. Hoe is het trouwens met Jasper?